Regression Adjustment (CUPED)

Regression Adjustment (CUPED) is only implemented for the Frequentist statistics engine, and is a premium feature.

GrowthBook aims to unlock high-velocity, enterprise-scale experimentation. Regression adjustment (also known as CUPED, short for Controlled-experiment Using Pre-Experiment Data) is one way to increase the velocity of experimentation by reducing the uncertainty in estimates of experiment uplift.

Why use CUPED?

CUPED decreases the variance of experiment uplift, increasing the accuracy of your experimental results and therefore the speed at which you can see the effects of an experiment. In the right conditions, CUPED can equate to getting 20% or more traffic during your experiment!

- In 2016, Netflix reported that CUPED reduced variance by rougly ~40% for some key engagment metrics (source).

- In 2022, Microsoft reported that, for one product team, CUPED was akin to adding 20% more traffic to analysis of a majority of metrics (source).

How does it work?

Regression adjustment (RA) in general uses data correlated with a metric to reduce our uncertainty about that metric and the statistics we compute. Any data correlated with the metric of interest, but uncorrelated with variation assignment can be used. GrowthBook (and many others) use pre-experiment data, as metrics collected before an experiment will not be affected by said experiment. In fact, the very name CUPED embeds this concept of using pre-experiment data. Using this pre-experiment data, we can fit a simple model to predict our outcome metric and use those predictions to adjust our metric. The adjusted metric then tends to have lower variance.

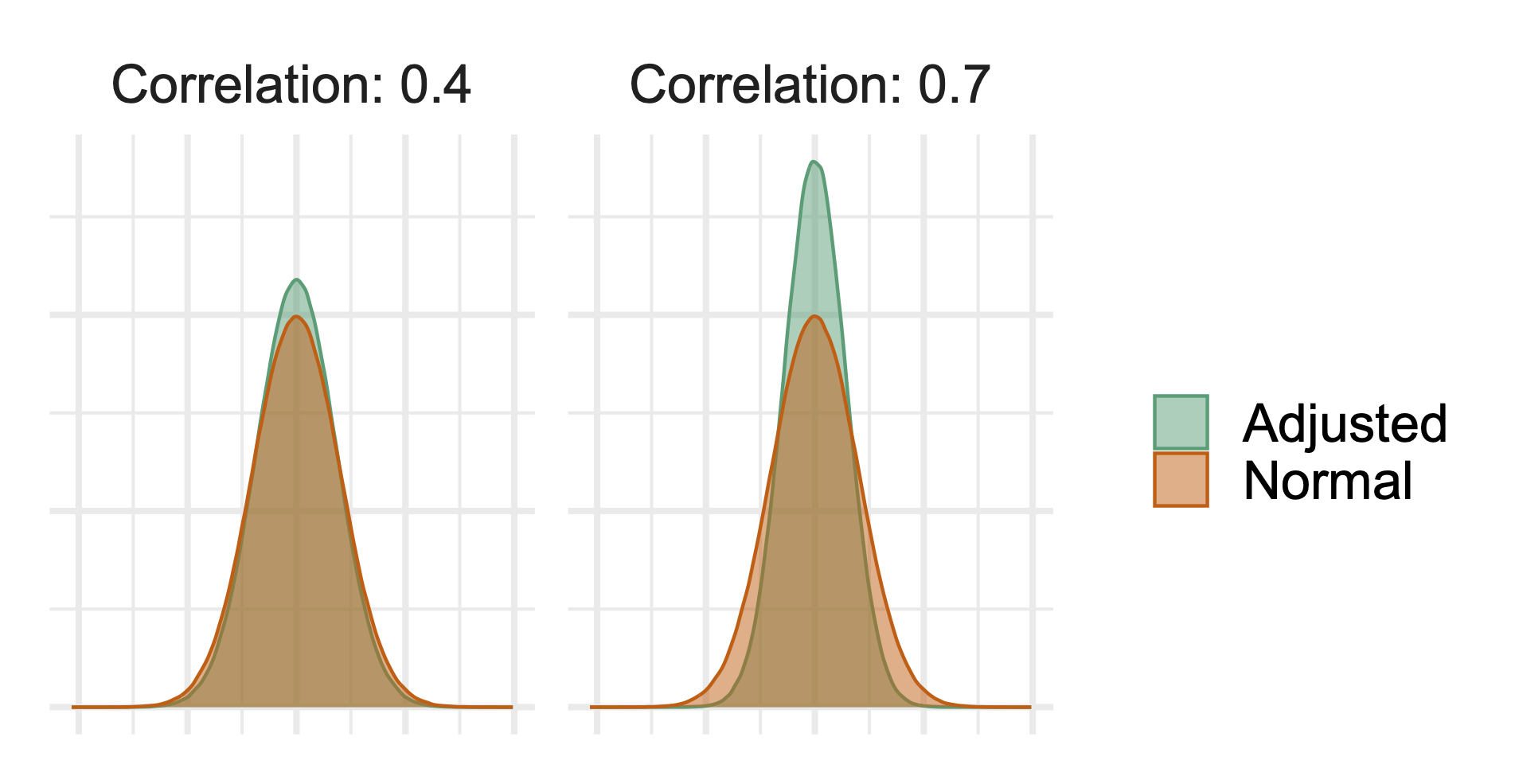

The more correlated the pre-experiment data is with your metric of interest, the more variance reduction you can achieve. For example, the following plot demonstrates the difference in the distribution of a metric before adjustment ("Normal") and after adjustment ("Adjusted"). In both panels, the green, adjusted metric is distributed less widely (e.g. it is more tightly spaced out around the mean). However, the adjusted distribution is even tighter in the right plot, showing that variance reduction will be greater the more correlated your pre-experiment data is with your post-experiment data.

In simpler terms, if we know a particular user tends to buy a lot of products on your website before you launch an experiment, we can use that information to understand whether purchase behavior after an experiment is driven by that customer's innate tendency to buy a lot of products or whether it was due to the experiment.

The concept of regression adjustment has been around for a long time, but you should feel free to read more in the original CUPED paper (Deng et al. 2013), a more general purpose paper on the underpinnings of regression adjustment from a sampling perspective (Lin 2013), and any of the many blog posts on the topic (e.g. Booking.com, Microsoft).

GrowthBook's implementation

GrowthBook takes a transparent, simple approach to CUPED.

For each metric you analyze, we use the metric itself from the pre-exposure period as the correlated data. This tends to be very powerful for metrics that are frequently produced by users (e.g. engagement measures), but can be less powerful if your metric is rare, or if you are measuring behavior for new users. In general, CUPED is more powerful the more you know about your units of interest and the longer they have been able to generate the metric that you are analyzing as a part of your experiment.

We then use the standard CUPED estimator for each variation mean,

where is the post-exposure metric average, is the pre-exposure metric average, and is essentially a regression coefficient from a regression of the post-experiment data on the pre-experiment data (pooled across both the control and treatment variation of interest), .

As discussed above, we could use any correlated data instead of . For example, we could use some model that includes all pre-exposure metrics added to your experiment, or auxiliary dimension information you have configured per user. However, one downside of these approaches is that your results for metric A will depend on whether or not you add a metric B to your experiment and our analysis pipeline would lose its modularity, where each metric can be processed in parallel. Nonetheless, we anticipate continuing to build methods that leverage additional data to improve variance reduction from CUPED.

Lookback window

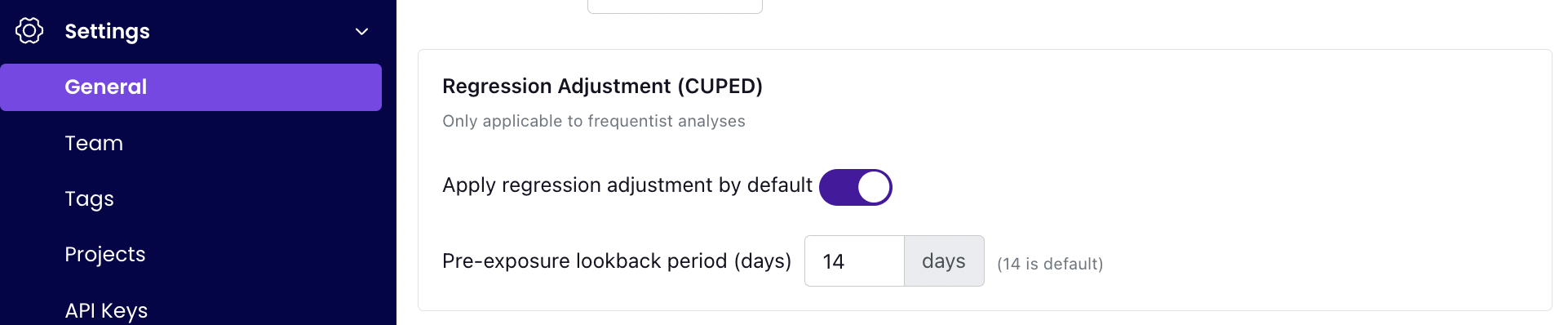

GrowthBook defaults to using 14 days of pre-exposure data, but this is customizable at the organization, metric, and metric-experiment level.

Why use a longer lookback window?

- A longer window can be better if your metric is low frequency and a longer window is needed to capture meaningful user behavior that will be correlated across the pre- and post-exposure time periods

Why use a shorter lookback window?

- Shorter lookback windows will yield more performant queries (fewer days to scan from your metric source)

- Behavior in the days just before a user enters an experiment is likely to be more highly correlated with behavior during an experiment, as users change over time. Of course, this is mostly true for metrics that are observed at a higher frequency (e.g. simple engagement metrics).

Availability

CUPED works for all metrics that are analyzed using the Frequentist engine, except for:

- Ratio metrics where the denominator is a count metric

- Metrics with custom user value aggregations

- Metrics from MixPanel and Google Analytics data sources

Configuring CUPED

Organization-level settings

You can turn CUPED on for all Frequentist analyses under Settings -> General. On that page, you can set the default behavior for metrics analyzed with the Frequentist engine. CUPED can be turned on or off by default for all analyses and you can set the default number of days to use for a lookback window. This setting will set the default for all of your metrics, which will then flow through to all analyses that use those metrics.

Metric-level settings

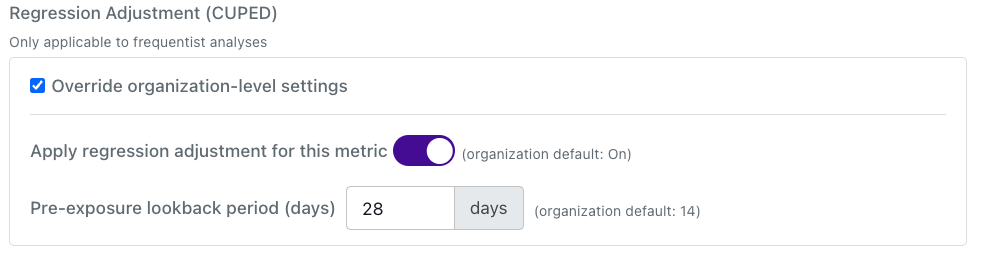

You can also override these organization-level defaults at the Metric level. When creating or editing a Metric, go to the "Behavior" panel, click "Show advanced options" and scroll to the bottom. From there, you will see the following settings. These settings will allow you to disable CUPED for a metric, even if it is set at the organization or experiment level.

You might want to disable CUPED for a particular metric if that metric never collects values for a user before they enter an experiment. You might want to adjust metric-specific lookback windows for any of the reasons listed in the section above.

Finally, you could also, if you wanted, override these metric-level settings for a particular experiment using metric overrides on the experiment page.

Experiment settings and results

By default, each experiment analyzed using the Frequentist engine will use your organization-level defaults, unless they are overriden by a metric. However, you can always toggle CUPED on or off for a Frequentist analysis using the new toggle added to the top of the results table. You may need to re-run your analysis if you change this setting.

- If the toggle is Off, then CUPED will not be applied to any metrics.

- If the toggle is On, then it will be applied for all metrics that:

- (a) it can be applied to

- (b) do not have a metric setting or metric override turning it off

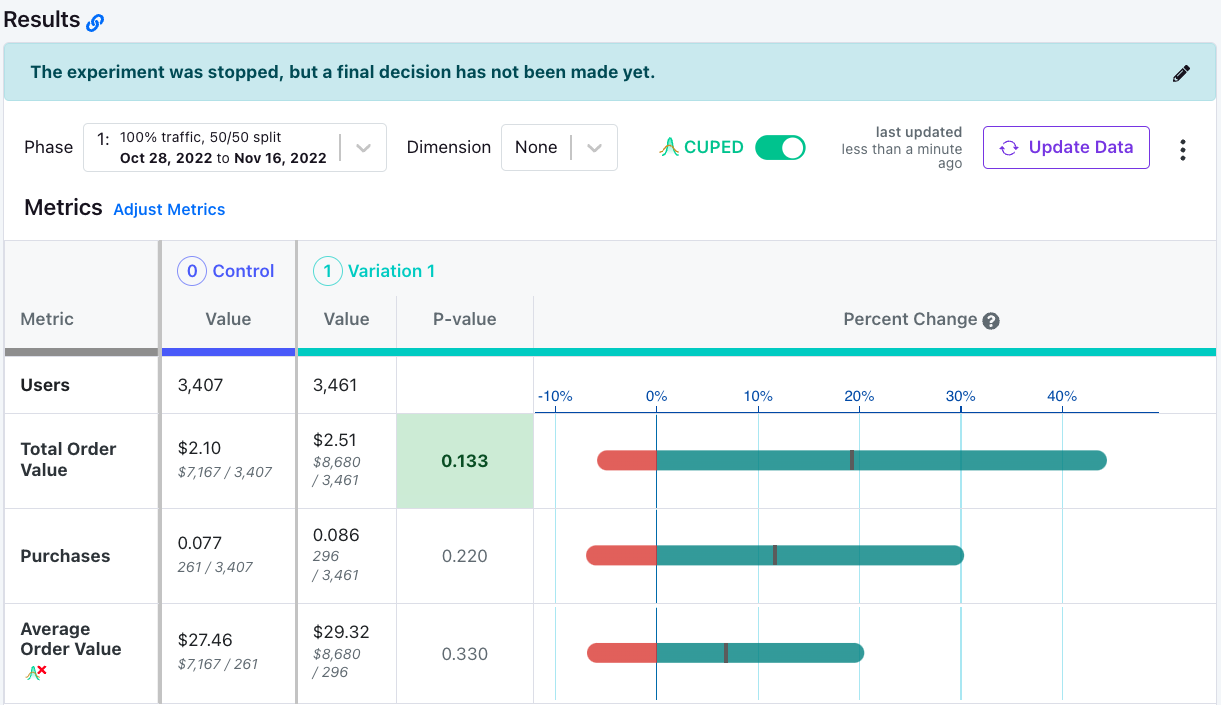

The following screenshot shows the results with CUPED on. However, you can see that there is an icon showing that CUPED is disabled for Average Order Value (because it is a ratio metric). So even if CUPED is toggled on, we will always show you any metrics for which GrowthBook did not use CUPED using that small CUPED icon with a red x.

Furthermore, if you mouse over the icon showing CUPED wasn't applied, you will get an explanation why.

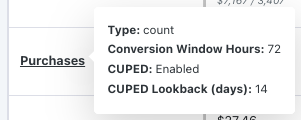

If you mouse over the metric name itself, you get the final CUPED status for each metric (on/off, number of lookback days).